I happen to be reading/re-reading two very different Manga at the moment (didn’t intend it that way, I just stumbled into it on discovering a new outlet): Silver Spoon and My Hero Academia.

I’ve talked about both of these before, but if you’re just joining us, Silver Spoon is a comedic slice-of-life series about a self-effacing boy from Sapporo who ends up attending a agricultural school in rural Hokkaido (that’s the northernmost island), discovering the vast, complicated world of farming and food production. My Hero Academia is an epic YA tale of a boy attending a school for superheroes and facing off with the forces of evil. So, pretty different, but with a lot of parallels. The one I want to talk about today is this: In both stories, the hero lives under the shadow of a patriarchal figure whose presence is one of the main driving elements of his motivation. But those figures make an interesting contrast.

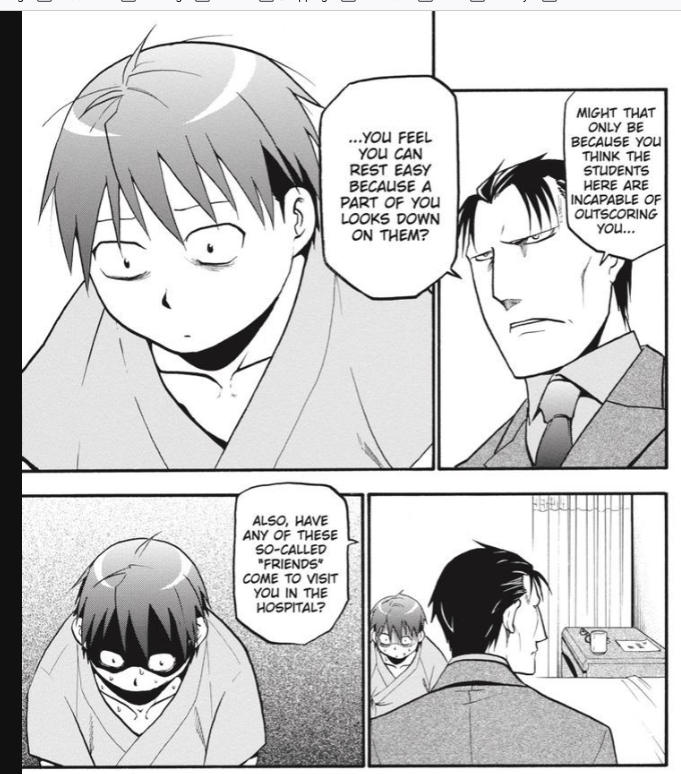

In Silver Spoon, Yugo’s main reason for coming to the farming school was to get away from his terrifying, demanding father, who expects his sons to excel and shows nothing but contempt when they fall short, even to the point of simply not getting top grades. He doesn’t shout or rage at them; he simply regards them with brutally cold disdain as he verbally tears down their excuses or pleas.

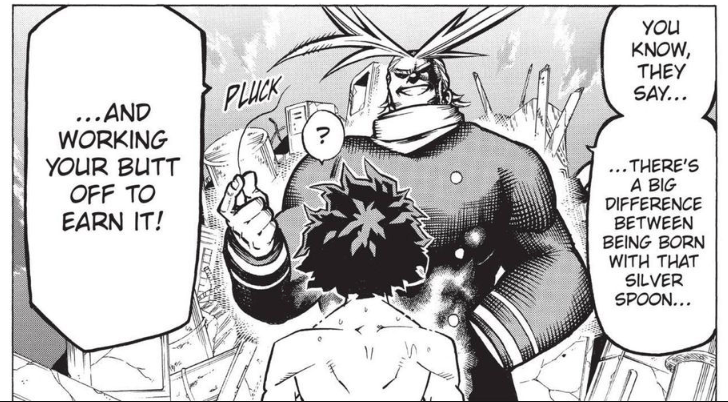

In My Hero Academia, on the other hand, we have All-Might, regarded as the greatest hero in the world (essentially this story’s version of Superman) and Izuku’s idol. Through a series of events he ends up selecting Izuku as his successor and proceeds to train and mentor the boy. He imposes a demanding fitness regime and is frank when it comes to critiquing or correcting him, but he does so with the constant reminder that he can succeed and that failures are an opportunity to learn how to do better.

Silver Spoon eventually makes it clear that Yugo’s father isn’t actually a bad man. He legitimately wants what’s best for his sons, only he has a somewhat warped idea of what that is and a terrible way of showing it. In Yugo’s eyes, he is purely demanding with the corresponding message that failure to live up to his expectations means that you are worthless; like farm animals who fail to produce enough to be profitable.

Meanwhile All-Might is demanding of Izuku (even over-demanding at times), but this is leavened by the fact that he also acts as a mentor, protector, and confidant to the boy, giving him the encouragement and positive reinforcement he needs along with the rigorous expectations. Izuku strives to live up to and exceed All-Might’s expectations not because he’s afraid of what will happen if he doesn’t, but because he loves and respects the man and is grateful for what he’s done for him.

In all this, it occurs to me that we have an image of the difference between the Protestant image of God and the Catholic one (at least, judging by their respective theologies: modern Protestantism kind of does its own thing).

In Yugo’s father, we have the implacably stern revulsion of the God of Calvin, looking upon mankind as utterly corrupt and worthless and setting a strict, straightforward condition for acceptance. Deviation from those conditions are not tolerated and personal effort is irrelevant. Hachiken-San, in a sense, could be said to regard his sons as fundamentally worthless unless they ‘cloak’ themselves in success (not a perfect analogy, of course, given the ‘Sola-Fide’ thing, though that does seem to come, in practice, with severe behavioral demands). Along with this is a strict practicality; as the old Puritans looked down on frills and frivolities like feast days or fine clothing or rich decorations, so Hachiken-San is disgusted to learn that his son worked himself to exhaustion for a mere school festival, not even related to his studies. He also coldly tries to deconstruct Yugo’s answer that he’s glad to be there because he has friends now, denying the reality of goods outside of his own narrow set of values.

In All-Might, we have the blazing love and goodness of the God of St. Francis de Sales, who blessed creation and called it good and whose heart burns with a love that spares nothing. All is demanded of each, but patience and encouragement is freely offered along the way to those who fall short, as long as they keep trying. Their persistence and willingness to continually learn and bounce-back is the really important thing, moreso than their inherent abilities (“In this battle, we are sure of victory if only we will fight,” as St. Francis de Sales says (par.)). Each is called to excel, but to excel according to their own state and condition. All-Might is simultaneously distant and awe-inspiring and humble and approachable. He shows implacable sternness to enemies, but patience to his students, even when they’re problem cases. Moreover, he considers their whole person, not just his specific demands, and encourages Izuku to take time to form friendships and enjoy himself along the way, as well as not to break himself in his efforts to excel. Moreover, these things aren’t separate from his vocation as a hero, but part of it.

(I’m positive this is coincidence, but I can’t help noticing that Hachiken-san’s demands take the form of incessant study and reading, while All-Might’s involve eating a portion of his flesh and building on the resulting gift…)

The father inevitably reflects an image of God. It may be a true image or a false one, depending on the particular father. It can also be illuminating in the other direction; how fathers are portrayed gives us an idea of how God is seen.

With that in mind, let’s take one more example from a more modernist piece of work: Elan’s father Tarquin from The Order of the Stick (that’s a very handy series, by the way, because it’s both pretty woke in its mindset and extremely well-written and engaging, which very, very rarely happens, so I don’t mind reading it and it gives me examples from the Other Side).

Tarquin doesn’t show up until the second half of the extremely-long-running (and still on-going) comic. To give a quick summary, Elan is the titular party’s bard, a dim-witted, childish, but lovable comic relief who spends a lot of time making self-aware comments on story structure. He has an evil twin named Nale who has been a recurring secondary-villain up to this point. Tarquin, it turns out, shares Elan’s awareness of storytelling tropes and applies them as a strategist, which has allowed him to become the de-facto ruler of several successive puppet empires.

His driving motive, as it turns out, is to control the world and people around him, to force them to follow their assigned paths as he sees fit for his own aggrandizement. He’s disturbed to find that Elan isn’t the leader of his party and tries to manipulate matters to alter that, and to force them into a plot where he is the main villain and Elan the main hero. He professes love for his sons, but is willing to kill them the moment he has to relinquish control of their lives, coldly dismissing them as ‘cluttering the narrative.’

Here, I think, is the modernist perspective of God: a petty tyrant with delusions of grandeur who seeks to force everyone in his orbit into a set box, moving as he sees fit according to arbitrary and outdated values, blended with a confused jumble of class pride and lechery. The triumph comes in breaking free and forging your own destiny and your own identity contrary to his will.

Or, to put it more simply, “God doth know that in what day soever you shall eat thereof, your eyes shall be opened: and you shall be as Gods, knowing good and evil.”

Fortunately, Elan has a more positive father figure in his mentor, Julio Scoundrel, though he doesn’t have much screen time. It’s significant that of the six leads only one (Durkon) has an unambiguously positive father…and his father died before he was born. Though he too gets a positive alternate in Thor – yes, that Thor: it’s a DnD comic – who starts out as a joke, but grows into a much more positive patriarchal figure as he becomes more involved in the story. Again, it’s a very modernist/woke mindset, but the author is good enough at his craft not to make it completely one sided.

In conclusion, I don’t suppose any of these examples are consciously made the way I’ve described them (well, maybe the last to an extent), but I do find the illustrations illuminating. Keep your eyes on fathers in fiction and think about what kind of image of God they suggest.