1. We’re still reading Thomas Paine in my American Government course (I’m going to be looking ahead this weekend, but I may have to go off-script because there doesn’t seem much else being discussed in the coming weeks), along with his chosen opponent, Rev. Charles Inglis (later the first Anglican Bishop in the New World). Interestingly enough, the kids agreed that Rev. Inglis was the more convincing, even though he’s arguing the side that ultimately lost out, just because he’s more logical and less, ah, exuberant than Paine (which is to say, Paine reads rather like he’s standing on a street corner screaming at anyone who walks by, and most of his arguments bear out the analogy).

2. But one point in Rev. Inglis I drew their attention to was his warning that England might counter Revolutionary America by giving Canada back to France and Florida back to Spain in order to threaten the Americans. Unlike Johnson (who mentions the idea sarcastically), Inglis seems to think it a real possibility. The point I wanted them to understand was that such a move would be politically impossible for the British. For their government blatantly to build up their ancestral enemies to keep its own subjects in line would be a move that no polity at any time would ever tolerate, even the ones who weren’t in sympathy with the Americans. Not to mention how it would affect their national reputation, position on the world stage, etc. Such a move would never have been seriously considered, however superficially appealing it might had seemed to some.

Which is the idea I wanted to get across: some things are political impossibilities, because while they maybe could theoretically be done, the consequences of doing them would be unacceptable.

3. This is the sort of thing that gets trotted out all the time as a dire boogeyman story to frighten gullible voters into action. There were, of course, plenty of examples on the other side, like the notion that the Quebec Act was ‘evidently’ intended to form the Catholics of Quebec into an army of conquest for the administration to use in subduing the thirteen colonies, and it’s been a feature of politics down to the present. Things technically possible (or even not possible), but which become ludicrous when you consider the consequences that must ensue.

Dr. Johnson cites ‘professing to be disturbed by incredibilities’ as one of the marks of the false patriot, and… yes, he’s exactly right.

4. Speaking of politics, my Classical History class is discussing Sparta and Lycurgus’s constitution. Honestly, for all their fearsome reputation, Sparta strikes me as exactly what you don’t do politically. They had universal suffrage, legal equality, no private property or luxury goods… basically a Marxist dream land. Except that the whole system rested on the backs of a massive slave population that outnumbered the Spartans themselves more than ten-to-one, which required them to spend all their time training to be the greatest military force in the world. Essentially, equality and common property were achieved by turning the country into one giant prison camp, where every citizen was a guard.

Which, of course, is why, despite their hyper-focus on warfare, the Spartans never did much conquering or expanded their territory. And rather embarrassingly, when it came time to fight the more artsy and intellectual Athenians, this nation of warriors got stuck in a twenty-year stalemate until the Athenians stabbed themselves in the foot (though of course there were reasons for that).

5. The point there isn’t “they were bad; they had slaves.” Everyone in the ancient world had slaves. Rather, the point is that the Spartan example implies that common property, legitimate equality, and so on can only really exist if you have a large subordinate population to do the necessary work.

6. Lately I’ve been listening to lectures by a gentleman calling himself ‘Apostolic Majesty‘, and I highly recommend him. His channel is focused on long-form historical lectures – one to three hours for most streams – from a Catholic Royalist, but frank point of view, full of detail, quotations, etc. (He also has some videos on Tolkien that are quite good, and his tear-downs of Braveheart and Kingdom of Heaven are delightfully entertaining).

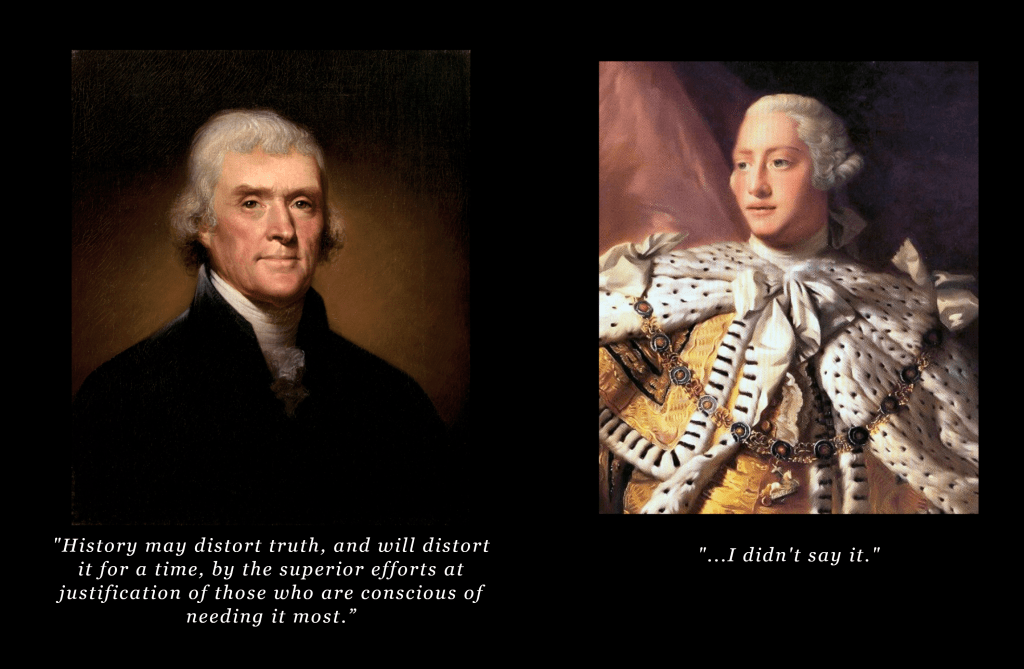

7. And let’s finish with a Loyalist meme:

It has long struck me how admired Sparta was, down to even modern times. What I’m missing, that the likes of Machiavelli wasn’t, was a sense of just how difficult it is to hold any government together for any length of time. So a Sparta might have been a hell-hole for all but maybe a few men at the top, but it wasn’t conquered not did it have endless revolutions for centuries. That fact, and not that 90%+ of the population were slaves, nor that the vaunted Spartan military existed primarily to keep those slaves in line, is what impressed people. To a guy like Machiavelli, who lived through part of centuries of Italian turmoil, with wars and slaughter a regular feature, just the fact that Sparta could keep a lid on things seems almost divine.

LikeLiked by 1 person

You know, I intended to add a comment that, despite all I say, they still lasted for hundreds of years (much longer than the Athenian democracy), so there must be *something* to be said for their system, but I forgot.

LikeLiked by 1 person