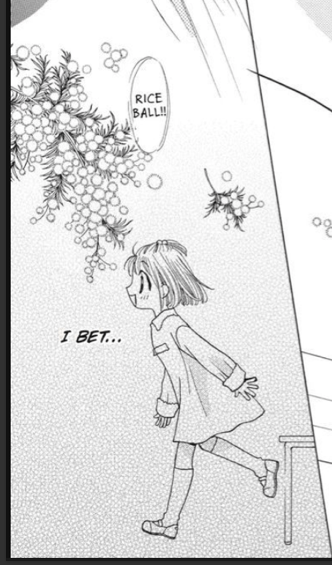

Fruits Basket tells the story of the romantic adventures of a rice ball in a basket of fruit.

Said rice ball is a cute, sweet, slightly ditzy teenager name Tohru Honda, while the basket of fruit is the Sohma family; an ancient, ultra-rich aristocratic clan with a tendency to extreme good looks and a strange family curse (there are also other characters, like her two best friends who I suppose would be…shell fish? Maybe some kind of hors d’oeuvres…the analogy sort of breaks down about that point).

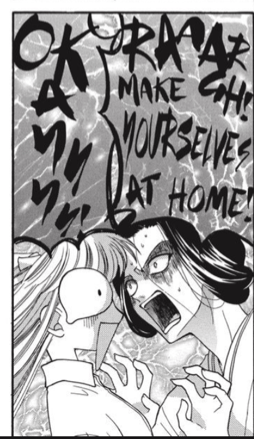

We meet our clumsily adorable, ricey heroine living in a tent in the woods. Her revered mother has recently died in an accident, and by a combination of circumstances and a severe lack of self-esteem making her unwilling to ask for anything for herself, she has nowhere else to go. One day, exploring the area, she comes across a house which turns out to belong to her classmate, Yuki Sohma, and his older cousin, Shigure and discovers that she’s actually camping on their land. One thing leads to another (e.g. she works herself into a fever and a landslide buries her tent) and they end up inviting her to stay with them, offering her the chance to pay for her room and board by doing the cooking and housework, which the two men sorely need (“I didn’t know we had a rice cooker.” “I uncovered it!”). Her moving in is interrupted by the abrupt arrival through the roof of another relative, Kyo, and by a quick series of accidents all three Sohma men end up transforming into animals.

Here Shigure fills her in on the core premise: certain members of the ancient Sohma family are possessed by the spirits of the Chinese Zodiac: Yuki is the Rat, Shigure the Dog, and Kyo is the outcast Cat (who doesn’t get a year because, according to the story, the Rat tricked him into missing the banquet). They transform into their respective animals when embraced by the opposite sex and have some limited power to communicate with their fellow beasts. After a brief period, they turn human again (“Totally naked, I’m afraid…”).

Before long, Tohru has become a permanent addition to the household and begins getting to know the Sohma family one by one. In the process, she begins to set matters in motion to possibly break the ancient curse once and for all.

Fruits Basket is one of those stories that’s grown on me imperceptibly over time. My first go through (in anime form) I enjoyed it, but only casually. Then I read through the Manga and liked it more. Then I found myself pulling up chapters for a quick dose of amusing cuteness, and before I knew it I’d gone through the whole thing three or four times. It’s a warm, cozy kind of story, fairly laid-back (though it doesn’t shy away from some harrowing subject matter), but satisfying and full of flavor. More fruit than rice, I suppose you could say.

As a matter of fact, there’s so much going on here that I’m probably going to have to do some follow-up essays to explore some of the themes in more depth, like the manga’s take on masculinity and femininity, sex, family, and so on. There’s some good meat here, though discussing any of those would involve a lot of spoilers. I’ll touch on a few here, but I’ll try to keep things mostly spoiler free (well, with one sort-of exception).

It’s a pure shoujo manga (aimed at teenage girls), so all romance, relationship, and character interactions, and coupled with some blatant fantasy elements (ordinary teenage girl gets mixed up with a high-class family largely composed of super-good-looking men who transform into adorable animals). All of which is pretty fun, but the success or failure of a story like this depends in large part on the quality of the characters. These ones are mostly great and a blast to hang out with, especially the leads. Granted, with such a large cast (our heroine, twelve-plus Zodiac members, friends, assorted family members, etc.), several characters fall through the cracks and end up underdeveloped, but overall the characters are one of the core strengths of the series. Which is good, since, as I say, it’s all about relationships and that mostly depends on how much we like being with them.

In addition to the main quartet mentioned above, the cast includes Tohru’s two best friends Uotani and Hanajima, who are respectively an ex-gang member and a goth psychic (giving them large enough personalities to match the Sohma clan and then some); her deceased mother (also an ex-gang member); Mayuko, their no-nonsense homeroom teacher who turns out to also have a history with the Sohma family; Kazuma Sohma, Kyo’s karate master and loving foster father (who isn’t part of the Zodiac); Momiji the Rabbit, a cheerful and unexpectedly perceptive boy who looks and acts at least four or five years young than he really is; Hatori the (ahem) Dragon, the family doctor whose intimidating face belies a kind nature; Kisa the Tiger, a very cute pre-teen girl who is initially too shy and traumatized even to speak until soothed by Tohru’s kindness; Haru the Ox, a spacey, but compassionate young man with a dangerously aggressive split personality; and Rin the Horse, an abrasive, shell-shocked young woman who has probably the most horrific backstory of the whole cast (which is saying a lot).

Then there’s Akito, the family head, and…well, it’s very hard to talk about him without spoilers. Suffice to say, he serves as the main antagonist for much of the story, and a thoroughly vile and frightening one at that, but a late-game revelation changes almost everything we thought we knew about him and re-contextualizes much of what came before. Most of the reviews I’ve read of the show (albeit that’s not a lot) give up and just spoil it, but I’ll leave it for now, and I’d recommend going in without knowing if possible. All I’ll say is that I think the story (and the character) is definitely the better and more interesting for the twist.

As I say, with a cast this large it’s inevitable some will fall through the cracks. Ritsu the Monkey in particular only shows up a bare handful of times, making it actually difficult to even remember he’s part of the cast on the first read through (the anime at least can show him in the opening and closings to remind you of his existence…assuming you don’t skip those like I usually do). Kaguya the Boar is a more regular presence, but her character essentially revolves around her hopeless tsundere crush on Kyo, and once that gets resolved she has very little to do. Your mileage will also vary on how funny her over-the-top assaults are (I thought they were extreme enough to be amusing, but a little goes a long way). That said, I do appreciate how they show her volatility as being distinctly un-attractive, driving Kyo away more than attracting him, and their understanding comes with her acting atypically calm and gentle. Kureno the Rooster doesn’t really become a major character until about two-thirds through, and while he has some interesting points, I found he didn’t leave as much of an impression as the others (Rin doesn’t join the cast until fairly late either, but she’s a lot more engaging).

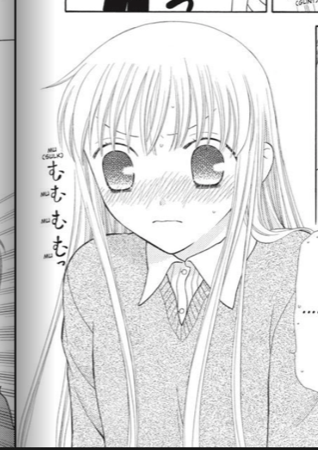

At the heart of the cast is our adorable human rice ball, Tohru, who is a simply delightful heroine. I don’t have a lot of familiarity with shoujo heroines so far, so I don’t know how out of the ordinary she is to the genre, but she’s ultra-sweet, charmingly clumsy, hard-working, cheerful, dutiful, and a bit of an airhead. She’s mostly played as self-effacing to a fault, but occasionally reveals a tremendous degree of unreflective courage, particularly in her interactions with Akito. As I say, the story is all about relationships with very little serious physical action, but it nevertheless does an excellent job of giving her the chance to showcase her heroic side, rendering her an atypical, but very worthy heroine.

And all the more so because she’s the kind of character feminists have nightmares about. Which is to say, she’s more or less played as being a thoroughly average person: she’s not especially smart or perceptive (she needs help studying and is often fairly oblivious to the world around her), physically weak (Kyo teases her for being skinny), prone to panicking or over reacting, and, at least at first, almost pathologically incapable of standing up for herself. In looks she’s portrayed as being pretty, but nothing extraordinary, especially compared to her two friends or to the Sohma women, all of whom are depicted as exceptionally beautiful. She’s extremely feminine, excelling in cooking and housework and cheerfully stating that marriage is a girl’s greatest dream, while whenever an argument or physical brawl breaks out she can only watch anxiously from the sidelines while stammering ineffectually.

Her only really outstanding qualities are her kindness and work-ethic, the latter mostly manifesting in her domestic work (even her part-time job is as a cleaning girl). Which is all kind of the point: Hobbit-like, her effectiveness as a heroine stems directly from her weakness and normalcy. Partly this is because malevolent people dismiss her as not a threat, but more so because her very humility and innocence is able to slip past people’s defenses and reach them where a more forceful or confident personality would put their backs up. As more than one character tells her, all she really has to do is be herself and that’s enough to help the people around her.

But that isn’t to say she’s a perfect angel or idealized fantasy figure. It becomes increasingly clear that, beneath her perpetually smiling facade Tohru has nearly as many issues as her friends.

Which is one of the points that makes the story – and especially the core romance – so interesting; that while Tohru is working to save the Sohma family and help them to deal with their psychological issues, she herself is in almost as much need of help as they are, as behind her cheery demeanor she’s unable to fully deal with her mother’s death, or with a number of other past traumas. She’s shown carrying her mother’s photo around and talking to it as if it were her real mother, and at first it seems like a charming quirk. But even before the first chapter is over, there are signs that it in fact represents an unhealthy reluctance to come to terms with her loss.

Even her kindness and selflessness isn’t always a good thing, as her crippled self-confidence makes it as much a matter of obligation as of generosity and leaves her with a tendency to neglect her own needs or to avoid asking for help, forcing her friends to figure out for themselves when she needs it. At one point, for instance, she goes out of her way to buy Valentine’s chocolate for all the Sohma men she’s met thus far, as a mark of gratitude for their kindness to her. It’s only afterwards that they realize she spent more than she could afford in doing so, leaving her behind in some of her school payments. If she makes a mistake, she sometimes worries to the point of making herself sick.

This all serves to make her an interesting and entertaining character in her own right, not just a blank slate point-of-view heroine, as well as to balance out her romance with Kyo by providing an opportunity for some back-and-forth, as she’s not the only one with something to give.

(That’s the one semi-spoiler I’ll give, by the way: that those two are the main couple. But really, it becomes apparent fairly early on, so I don’t feel too bad about it)

You may have noticed from the plot description that there’s more than a touch of The Sound of Music to the story; a perky lower-class girl gets brought into a rigid aristocratic family milieu where she proceeds to inject some much-needed maternal care while sparking a romance with one of the men, with a cheery surface set against a background of grim shadows (more on those shadows in a bit). One key difference, of course, is that Maria is a self-possessed, take-charge, plucky young woman, while Tohru, as noted, is awkward, self-effacing, and almost devoid of self-confidence. But one arguable flaw in Sound of Music is that the romance is a little one sided; Maria is largely the one giving what the Captain needs, while he doesn’t really have much to offer her in return except a home. It’s not a major flaw (and the charisma of the leads helps to make up for it), but is a bit of a lack. Here, on the other hand, Tohru’s weaknesses mean that Kyo has something to offer her as well, and the two are able to form a very charming, mutually supportive, complementary relationship.

Our two male leads are both solid characters in their own right, not to mention it being a little unusual that a romance has two equally important male leads, yet doesn’t really go for the love-triangle aspect. There’s a little bit of that in the early stages, but never to the point of it becoming competitive, which, considering how much the two already hate each other, is a pretty clever piece of foreshadowing of what’s really going on here.

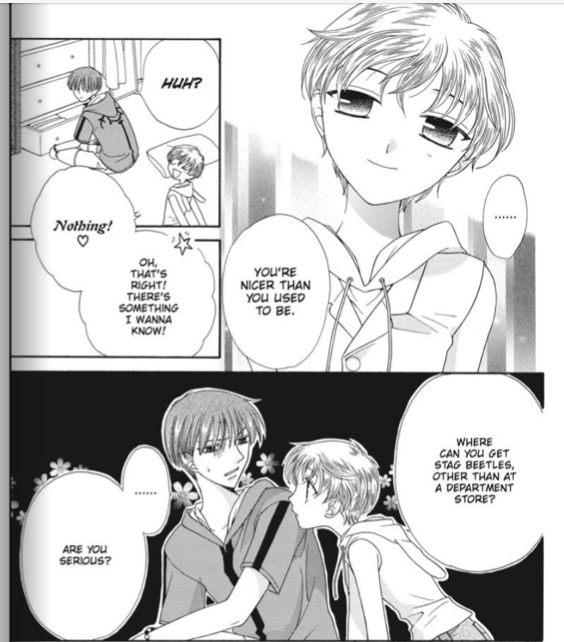

Yuki’s the popular, superficially perfect one; good-looking (to the point where he’s sometimes mistaken for a girl and has an obsessive fan-club at school), athletic, intelligent, and courteous, so much that his classmates nickname him “The Prince”. But he’s also very reserved (he initially feels the need to leave the room in order to laugh out loud at Tohru’s antics) and as he opens up to Tohru he reveals a crippling lack of self-esteem and lingering PTSD from the abuse he’s suffered at Akito’s hands, accompanied by jealousy of Kyo’s ability to mix with people. A large part of the story is his growing out of his weak, reserved state into a more mature, confident personality.

Yuki eventually gets his own sub-plot – almost a sub-series really – of him becoming president of the student council and having to manage the various oddballs and eccentrics who are the other members, in the process putting the things he learned from Tohru into practice by developing his own friendships and reaching out to help someone else in need. This is mostly unconnected with the rest of the story – to the point where it feels almost like a crossover event whenever the student council members interact with the zodiac characters. Not that that’s a bad thing, as part of the point is that he’s moving beyond the family circle.

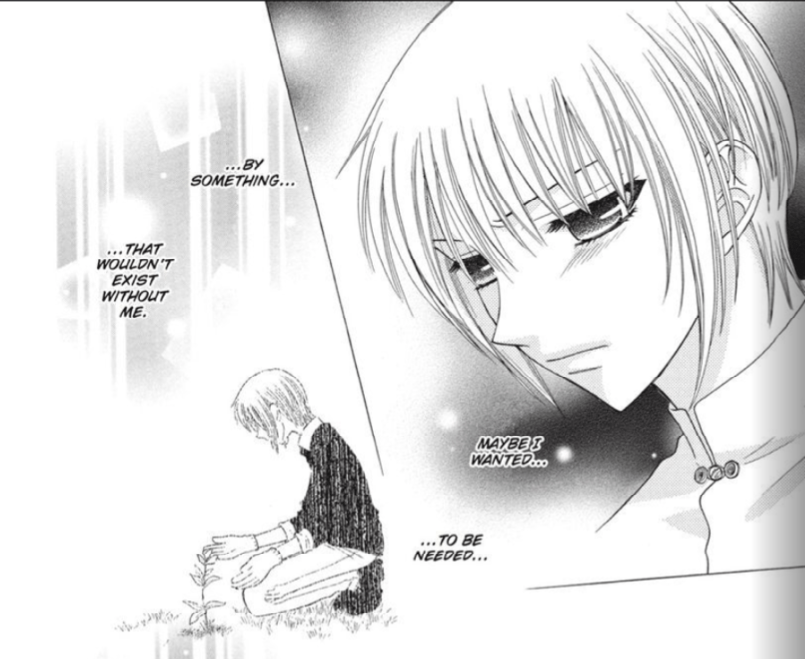

On that note, I really like how Yuki at one point explains that he doesn’t want to be with someone he’s emotionally dependent on, but with someone he can help and care for (following an idea he already expressed regarding the vegetable garden that initially provides his main outside interest: “Something that wouldn’t exist without me” as a counter to his feelings of worthlessness). It’s a smart, insightful bit of psychology setting up his own romantic subplot.

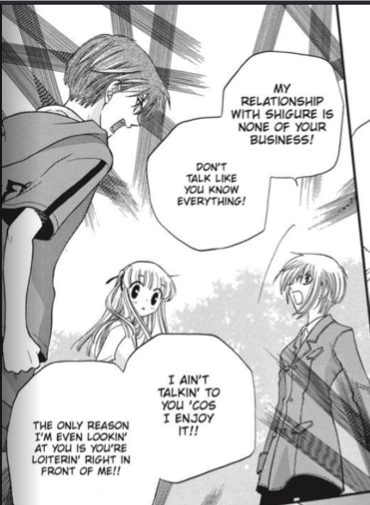

As for Kyo, he’s the rough, aggressive one of the two, reacting to his trauma and exclusion by being almost constantly angry and sullen and trying to pick fights with Yuki that he inevitably loses. Initially there’s a pattern where he’ll snap at Tohru, then catch himself and hastily try to reassure her.

In his case, the curse is worse than anyone else’s, as the Cat is meant to play the role of scapegoat (in the myth recounted at the start of the series, the Cat is tricked into missing the banquet of animals by the Rat), and he’s been excluded from the family and ill-treated his whole life (his curse also has some additional features, but we’ll leave that for now). At the same time, though, he turns out to be more sociable and approachable than Yuki, once he gets a little accustomed to people, and fits in well with Tohru’s two friends (who tease him mercilessly, but affectionately).

His gruffness also hides a protective streak a mile wide, which comes out any time Tohru seems in need of help, whether scaring off potential harassers or just listening to her problems and anxieties. Or, in a memorable moment early on, letting her know that it’s okay to complain sometimes and to be honest about what she wants rather than hiding her feelings for fear of being a bother. In short, he shows early on that, beneath his prickly personality, he really is a kind and caring young man, just beaten down by life, but with a great capacity for compassion.

As I say, the above really adds a lot to their budding romance, giving our heroine as strong a reason for falling for him as he has for falling for her. Again, there’s enough here to sustain its own essay, so I won’t go too far into details this time.

Then, of course, there’s the relationship between the two young men, who, for most of the story, legitimately hate each other. In the early chapters they’re almost constantly fighting (with Yuki winning every time), and even once that dies down they’re frequently at each other’s throats. Yuki in particular becomes almost a different person around Kyo, all-but bullying him at times.

Underneath, however, we’re shown that they’re actually very similar, even frequently having the exact same thoughts on the events around them. And the reasons behind their mutual hatred turn out to be less due to their actual personalities than a matter of mutual envy and psychological coping (that is, each was so miserable growing up they almost had to project it onto someone else), but that only makes it more intransigent.

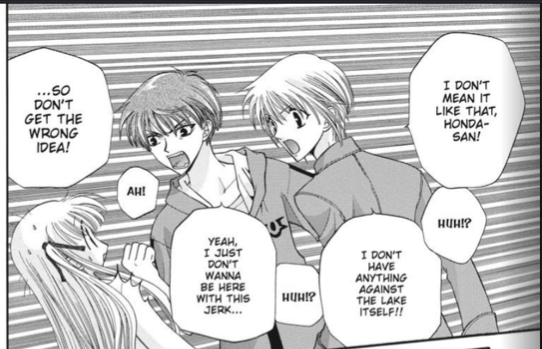

Which all makes their mutual care for Tohru and moments of grudging cooperation on her behalf all the more impactful. They may hate each other, but they both care for her, and this slowly, but steadily begins to soften their animosity simply because they now have a common interest and are constantly being dragged along with their now-mutual friends so that they can spend time with her. There are several times where they start going off on one another, only to recall that she’s in the room and hastily back off so as not to worry her (I do like that, for a long time, she doesn’t try to intervene; she only stands on the sidelines making ineffectually anxious faces. It’s not about her leading them, but her drawing them).

Then there’s Shigure, the ostensible adult in the room, a shiftless writer of trashy romance novels, and probably my favorite character in the story. I’ve gone through the series multiple times by now, and I’m still not really sure just how much of his character is genuine kindness and how much is him being a selfish, sleazy bastard. Because there’s definitely a lot of that latter category. He’s fun because he’s not only a major source of humor through his playful, teasing, immature behavior, but also because there turns out to be a lot more to him than initially appears. As the story goes on it becomes clear that he’s a lot smarter than he lets on. In fact, he’s far and away the smartest character on the board and is manipulating events for his own purposes, though just how much he’s doing so only becomes apparent on subsequent read throughs.

This cunning is wrapped underneath at least two personas; one a surface-level indulgent, lazy kindness that only Tohru really falls for, while the second is that of a selfish, childish sleazebag, which is how most of the other characters perceive him, resulting in a lot of very funny vignettes where he plays the others like a fiddle with everyone except our heroine being completely aware of what he’s doing, but falling for it anyway (“You wouldn’t let me go on a trip with Tohru alone, would you?”).

(It’s a mark of how oblivious Tohru is that she doesn’t even have an inkling of his real personality until he flat out shows it to her).

Though it’s clearly not all selfishness; he’s shown to be very generous, especially toward Tohru, occasionally stoops to giving some legitimately wise advise (albeit punctuated by goofball antics), and on the few occasions where he has the opportunity to cross the line into unmistakably villainous territory, he remains firmly on the right side, seemingly without a second thought.

I really like characters who are sort of bastards, but ultimately on the side of the angels, and I also like characters who are smart enough to go toe-to-toe with vastly more powerful opponents through wits alone, and Shigure is both of these.

Another one of my favorite characters is Ayame the Snake, Yuki’s flamboyant, eccentric, and semi-estranged elder brother, who very deliberately steals the show every time he appears. Ayame presents as an extremely self-centered, vain, campy moron given to flowery purple speeches and possessed of an overwhelming personality. But then, in his very first appearance, just as we’re laughing and shaking our heads over his antics, he reveals a sincere sorrow for his past neglect of his younger brother and that his greatest wish now is to somehow repair their damaged relationship. Which is to say, underneath his flamboyant and absurd exterior, Ayame proves to be a genuinely kind and loving man who cares deeply for his brother, even if he generally chooses ridiculous ways of showing it (“I christen this day Yuki’s Lustful Awakening Memorial Day!”). He also proves to be touchingly devoted to his equally eccentric girlfriend, Mine, with whom he sometimes reveals a more somber and serious side to his personality.

Though the series makes it clear that Yuki has good reason for resenting him, as we learn that Ayame truly was self-centered to the point of being cruel in the past (and not only toward Yuki), a fact that he only came to realize as he matured and fell in love. Again, I like that sort of superficially stupid and selfish character who proves to have deep wells of kindness and love beneath their goofy exterior, and characters who are trying to atone for serious mistakes in their past. There’s something deeply heartwarming in how delighted Ayame is even to have Yuki be angry at him, because it means that his brother still feels something for him. Even more so are the rare moments where he gets serious and truly comes through for his little brother. Plus their interactions are often extremely funny as Yuki futilely tries to rein in Ayame’s flamboyant antics.

And a third favorite is Hiro the Sheep, an arrogant and rude twelve-year-old boy who acts downright mean to Tohru when we first meet him. But before long it becomes clear that he’s not actually so much mean-spirited as he is trying to be mature and confident without really knowing how, as well as working out his frustration at not being able to protect the people around him owing to his young age and the effects of the Zodiac Curse. In particular, he’s in love with Kisa, but was unable to do anything to help her when she was being bullied and abused and so takes his anger at himself out on other people, especially Tohru (who was able to help her).

Hiro’s a really good example of a character who is often unpleasant, but from mental scarring and immaturity rather than genuine arrogance, and who convincingly comes across as sincerely wishing to be a good person, just not being very skilled at it yet. It helps that he often is shown beating himself up over his own bratty behavior, and that he really tries to be kind and protective to shy little Kisa. He’s one of the characters who matures the most over the course of the series, slowly graduating to a deadpan straight-man, and gaining an adored baby sister late in the story.

Momiji the Rabbit is also a pretty interesting character. As noted, he looks and acts like a little kid for most of the story, offering a lot of bright, cheery antics, but he also evinces one of the most mature perspectives of any of the characters whenever he gets serious, and when push comes to shove is one of the more reliable members of the cast. There also turns out to be a bittersweet tone to his character arc, as his more mature side comes out more and more.

I also really like Tohru’s two friends, who are an absolute blast for how strong their personalities are. They end up serving as a cross between surrogate parents and self-appointed body guards to her, leaving most of the rest of the cast mildly terrified of them. As noted, Uotani is an ex-gang member, while Hanajima has psychic powers and a dreamily abstracted, yet commanding air that leads to some great moments (“And I am the hawk that swoops in to steal this sugary confection”).

Refreshingly, this means that although Tohru is exactly the kind of character who would be bullied (and was in her backstory) that isn’t really a factor here, at least as far as she’s concerned, since, while there are plenty of mean girls around who would like to give her a hard time, especially Yuki’s fan club, her two best friends are constantly scaring them off (which is a running gag in itself: “Don’t bring a metal pipe to school!”). Their protectiveness extends to even perceived slights against her, such as when the two girls flare up with ominous fury at Yuki and Kyo’s perceived lack of enthusiasm at the suggestion that one of them might marry Tohru.

It’s a fun dynamic to have our ultra-sweet airhead flanked by this pair of intimidation factories, though it’s also extremely sweet and heartwarming as we get to see their backgrounds and understand why they value her friendship so much and defend her so fiercely. At the same time it cements the idea that the caring, almost motherly character she shows to the Sohmas is just who Tohru is and what she does naturally.

Also, the fact that Hanajima is psychic lends credibility to Tohru’s ability to take the Sohma curse in stride. This isn’t her first supernatural encounter, albeit more dramatic than her friend’s, so it makes sense that she would be able to process it. Especially coupled with the ditziness that leaves her more or less willing to accept whatever’s presented to her.

Then there are the school classmates who mostly flit in and out of the story, including the Yuki Fanclub girls, who get some big laughs in the first two-thirds or so (and a few touching moments as they begin to leave the story). And, as noted, in the second half Yuki becomes president of the student council and gets his own supporting cast of eccentrics to manage, including Kakeru, his vice-president, who insists on treating the student council as if it were a ‘Power Rangers’ show (“I’m Black. That’s the only thing I won’t budge on”), his shy, half-sister Machi, who compulsively wrecks anything that’s too neat, and Kimi, who is…well, just plain one of the funniest characters in the series (“Kimi hates spending money on anyone but herself!”).

You might have gathered from the above that the story has an idiosyncratic sensibility, very much with its own tone and sense of humor. Things like Hanajima being psychic: why? Are psychic powers a thing in this world? Never explained; she just happens to have these powers, and her brother may or may not be able to curse people. She’s also mildly obsessed with food (“If we just show up, they may not be able to serve tea and snacks”) and at one point blows off a marathon race in gym class in favor of first reading one of Shigure’s dirty novels and then setting up a poker game that somehow ensnares half the class, including the gym coach himself.

That’s the sort of off-beat humor and characterization that show up again and again, and which helps to make the story so much fun. Or things like ‘Mogeta’, the occasionally seen Pokemon-like anime that some characters are big fans of while others can’t stand. I also love the occasional fourth wall breaking captions in the manga clarifying points in a semi-sarcastic manner, e.g. “This is Tohru’s hair” or “Wasn’t paying attention” or “This is a Shoujo manga”.

There’s a running gag of Shigure’s house getting wrecked one way or another (usually by one of the other characters throwing a tantrum). Or the fact that Tohru’s co-workers have no idea who Momiji is however many times he invites himself to join in (his father owns the building they’re cleaning). Or Ayame trying to call Hatori to report minor progress in mending his relationship with Yuki (usually mere seconds after the fact and while Yuki is standing right there). Or Shigure torturing his editor by pretending to miss deadlines. Or, in the manga, the fact that panels showing the guys walking around school usually have a random, heart-struck girl or three in the background.

As noted, there’s also a bit of a recurring gag of Shigure being sleazy while Tohru’s none the wiser, so she’ll be mentally exclaiming over how generous and kind he is for, say, volunteering to fetch her things from school, while he’s inwardly gloating over the prospect of ogling her classmates. Or another one of the more cynical characters will Tohru of trying to manipulate them, only for her to immediately put her ditzy nature on full display.

One of the funniest chapters involves part of the cast putting on a production of ‘Cinderella’ as their school play, which very quickly goes completely off the rails into a largely-improvised parody (“Burn the ballroom to ash.” “That would be a crime. Wish for something more wholesome”).

As I say, the humor is mostly a matter of characters sparking off each other and of the idiosyncratic flavor of the story coming to the fore. Personally, I found it a lot of fun. Not just funny, but the rather more elusive quality of being charming and grin-inducing. Though personally I found one of the funniest and most endearing elements to be just the amazing faces that Tohru makes whenever she’s panicking or shocked or flustered (which happens a lot). Granted, that’s a manga / anime trope, but this is gold-standard, top-drawer face-faulting and off-model cuteness as far as I’m concerned. I can’t get too much of that stuff.

Though like a lot of Japanese media in my experience, the series isn’t afraid to mix bright and cheery humor with painfully realistic depictions of human horror. Though it thankfully doesn’t get as dark as it could have, it does deal with some pretty horrible material, like psychological trauma, child abuse, bullying, suicide, and so on (though, sadly enough, it could easily have gotten a lot darker if the author had wished: there’s no sexual abuse depicted, for instance. At least, none directed at children). The main thrust of the story is, in fact, dealing with trauma and suffering and learning to overcome it and move on. To that end it goes into some pretty dark places. As noted, Rin’s backstory is particularly harrowing, especially underlined by her subsequent emotional state (the chapters told from her point of view are notably less coherent than the others, reflecting her tortured mindset), but Momiji’s and Hatori’s are also notably tragic and horrible, as is Hanajima’s. Indeed, it’d be easier to note the major characters who don’t have some kind of explicit major trauma or tragedy in their past (basically Hiro – though he has a strong burden of guilt, Kaguya, Shigure, Mayuko and…that might be it).

Again, it isn’t as grim as it might be, and we don’t see anything explicit, but it gets pretty heavy at times. It’s also noteworthy that even well-meaning characters are sometimes shown to inadvertently make things worse through poorly-considered responses or because they’re not able to see past their own trauma to recognize the pain in the other person. It is almost a running theme that mere good intentions aren’t enough to stop one person from hurting another, and even thoroughly selfless actions can prove to have been the worst possible choice.

As that indicates, I found there to be a thoughtfulness and nuance to the story’s take on these issues which is often missing. This extends into things like the reasoning behind Yuki and Kyo’s mutual hatred and its depiction of how Tohru begins to bring healing to the family, which, as I say, is pretty much simply through being her gentle, compassionate, unaffected self.

This manifests in two ways. Most obviously, her kindness gives her friends the kind of support and emotional security that they’ve been lacking. They find her as someone whom they can open up to without reserve, sharing their hurts, fears, and anxieties with and receiving sympathy and understanding in return. That is to say, she provides them with the kind of emotional refuge that ordinarily comes from parents and family, which most of them have never known (interestingly, the Zodiac member who is least fond of her – Hiro – is also one of the few with a loving, stable home life).

Equally important, as it turns out, is that she gives them someone to care for; someone to take their attention off of themselves and their own problems and sacrifice and struggle on behalf of. This first manifests when Yuki and Kyo – who, again, previously couldn’t be in the same room without fighting – actually team up to go rescue her from her horrible relatives when she temporarily moves out (they bicker the whole time, but they go nonetheless). As noted, the fact that they both care for her, however much they dislike each other, is enough to get them to, grudgingly, cooperate more and more. Not only that, but both of them begin leaving the house and going into public, on day trips or dates or the like, just because they know it’ll make her happy.

Slowly but surely, this begins to extend to the rest of the family, as Tohru’s kindness brings them out of themselves and begins to help them to heal, not only internally, but in their relationships with one another. The fact that everyone cares about and likes her means that they begin to notice first one another (at one point it’s mentioned that they never really used to hang out all together before she came) and then other people. Their concern for her summons them to unexpected heights of kindness and courage, as when cheery, childlike Momiji actually stands up to the terrifying Akito to try to protect her. And of course this is already in place with her two best friends who are both ferociously loyal to and protective of their little friend.

One of the best aspects of the series is that, even though it deals heavily with the darker manifestations of family life, it doesn’t attack family life as such. On the contrary, a real, loving, intact family is exactly what the characters long for and which they struggle to build or rebuild. The story knows that the twisted circumstances on display are not the norm, but a corruption on something fundamentally good. Which is why the answer isn’t full-on rejection, but healing and moving on.

On that note it’s important that, while abusive and unhealthy family situations form a major part of the story, it isn’t the least monolithic or one-note in its portrayal as so many other contemporary stories are. On the contrary, we get a pretty good cross-section of the different kinds and degrees of family life, from the exemplary to the monstrous and almost everything in between. Some characters have parents who are abusive to the point of being dangerous to them (e.g. Rin’s parents, Kyo’s biological father), or who are criminally negligent (Yuki and Ayame’s mother) or become broken by the experience of the curse and reject their children (Momiji’s mother), but we also have exemplary, caring parents on display (like Hiro’s mother, Kyo’s adoptive father, Hanajima’s parents, and of course Tohru’s own late mother).

Still others fall somewhere in between, like Ritsu’s loving, but emotionally unstable mother whose incessant apologies on his behalf contributed to his ultra-low self-esteem, or Kisa’s mother, who loves her, but whom we find exhausted from the strain of raising her cursed daughter, requiring them to spend some time apart to heal (during which she calls to anxiously check on Kisa and tell Tohru her favorite foods), or Uotani’s recovering alcoholic father. The story doesn’t draw a line between “perfect parents” and “bad parents,” but showcases a sympathetic range of different outcomes. The main distinction, it seems to be, is whether the parents continue to love their children, regardless of the difficulty or strains or mistakes made.

As far as criticisms go, I’d say my biggest issue with the series is that the main gimmick – of turning into zodiac animals – is so underused. It only really forms a major part of the story in the early chapters, and after a while it becomes an afterthought. Most of the characters (however important) only transform once in the whole series, and they only really play with the device a few times in the early stages before more or less leaving it alone.

Granted, the story had other priorities, but even so I think the balance could have been handled better. There is so much fun potential in the idea that it’s disappointing that more isn’t made of it.

Nor is there much effort made to connect the personalities of the characters with their respective animals. That is, sometimes they do, sometimes they don’t; Kyo the cat is aloof, but loving when you get to know him, Momiji the Rabbit is energetic and affectionate, Haru the Ox is strong and hard-wearing, Hatori the Dragon is wise and authoritative, Rin the Horse is spirited, but delicate and so on. On the other hand, though, Yuki the Rat doesn’t really have any rat-like qualities (he’s clever, but he’s more responsible and thoughtful than guileful), Ayame the Snake is the reverse of solitary and subtle, and Shigure the Dog is sly and manipulative with highly limited loyalty (honestly, those two could have easily been reversed and it would have made more sense). Ritsu the Monkey isn’t at all clever and curious, and so on. In at least one case there seems to have been a deliberate effort to reverse the characters: Kisa the Tiger is shy and gentle, Hiro the Sheep is proud and aggressive.

Generally speaking, I’d say the whole Zodiac motif could have been much better and more extensively utilized. As it is, it almost gets lost amidst the psychological intricacies and relationship issues of the second half, and the curse becomes chiefly a matter of the Zodiac members’ connection with Akito, with the transformation and animal aspect nearly forgotten.

On that note, the rules and manifestations of the curse are not always very consistent; early on Tohru triggers it just by bumping up against the boys, but latter characters are able to get close without transforming so long as they don’t actually hug, and in any case they tend to seem a lot less concerned about it than they probably should be (e.g. I’d think that Yuki would be afraid to be in the same room as someone as exuberantly uninhibited as Kimi, but he doesn’t seem to even think about it).

Then, when the curse does break, it isn’t exactly clear why. You can work it out the reason from clues in the story, but it’s not made explicit, and in any case the sequence of when it breaks and for whom seems to have little rhyme or reason beyond the demands of the story. As a matter of fact, at one point it seems to be setting up for a particular character to break, with a very dramatic scene of rebellion, but then he doesn’t and someone else does instead; why? But I can’t really go into that any deeper without spoilers.

Likewise there are a lot of other factors going around that are just part of the pattern, but don’t really have payoffs. Hanajima’s psychic powers, for instance, never really play into the plot one way or another; it’s just a character quirk. Even though you’d think they would perfectly suited to match with the Zodiac curse. In general far fewer characters learn about the curse or directly interact with it than I was expecting, which again is not really a problem, but it feels to me like a lost opportunity, just because of how strong the characters are. It would have been a lot of fun, and a chance for a more dramatic show of loyalty, to see people like Tohru’s two friends or Yuki’s new student council pals (or some of them at least) come to terms with the curse and help the Sohmas deal with it. But that’s more subjective than anything, and it may have damaged other elements if they’d gone that route.

And, especially in the manga, the pseudo-philosophical ramblings about healing and love and family and so can run on rather long and sometimes feel a little shallow. As I say, there’s some very good stuff here, but there’s also some not so good stuff, and all of it arguably gets overdone at times. Fortunately, in the manga at least, you can always just skim ahead if you like.

There is a little bit of inconsistency with regards how backstories are described versus how they’re later depicted in flashbacks, especially regarding Tohru’s mother. She’s initially described as a legendary gang leader, but we later learn she left the criminal life after Middle School; could she really have achieved that status at that age? It wouldn’t be an issue, except that another character’s backstory is partially dependent on it and it seems such an easy problem to avoid.

Another issue (albeit one that only occurs in the manga) is that, unfortunately, the artist isn’t as skilled at doing different faces as some other artists, and most of the cast are supposed to have a strong family resemblance, meaning that some of the characters end up being difficult to tell apart at a glance, especially in the black-and-white manga pages. This is particularly a problem in the later stages after Momiji has a growth spurt and becomes at times nearly indistinguishable from Yuki.

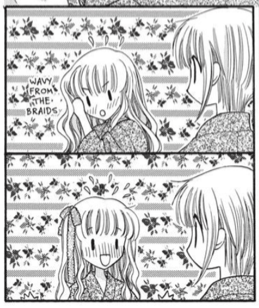

Speaking of which, the art noticeably improves over the course of the series, going from the rather angular-looking characters of the early chapters to smoother, more detailed depictions later on.

That said, I think I like the manga overall better than the anime. They’re mostly the same, though the latter rearranges a few things and alters some episodes, usually to good effect, but the third season in particular cuts out and condenses a lot of material from the final part of the story that I think gives it a more complete and satisfying story shape (Yuki’s side-plot suffers especially from this, and we lose the backstory of Tohru’s parents, rather undercutting part of the ending). It’s still a coherent story, but I prefer the more complete version.

The anime also makes a few more significant changes to the lead up to the ending, apparently to try to correct some less-than-perfectly convincing aspects of the climax. Though honestly I think they remain kind of a stretch in both versions, so I don’t know that it was really necessary (actually, on reflection, I think the Manga version was more believable in both cases, so…oh well). It’s not bad, just kind of unnecessary.

(Though the anime does have one of my favorite lines in the whole series, which isn’t in the manga:

Hanajima: “Are you and [Yuki] dating?”

Tohru: “No! Nothing like that! I just live with him, that’s all!”)

Speaking of which, I should note that there are actually two anime series; one that came out in the early 2000s and only covered part of the story, with a different ending, and another that came out in 2019 and covered the whole thing: so far I’ve only seen the latter.

Then there are some points that are rather uncomfortable, like the large age gaps between some of the romantic pairings (including Tohru’s parents, as it’s revealed her mother was only sixteen when they married. Granted, she didn’t have anywhere else to go, and maybe Japan feels differently about these things, but it’s a little weird nonetheless, not to mention the aforementioned continuity issue). And then some mild to moderate sexual matters, mostly reasonably framed as unhealthy reactions to the curse (e.g. Ritsu’s cross-dressing), but there’s also things like Ayame’s shop catering to ‘men’s fantasies’, which I found to be more funny than anything but given it’s obviously a roll-playing costume shop could reasonably raise red flags. Though honestly, Ayame and Mine are both too over-the-top and, well, innocent in a way for it to really come across as immoral, especially since all the other characters take a dubious view of the enterprise as a manifestation of the ‘skewed reality’ they occupy. That said, their costumes aren’t really revealing or overly sexy from what we see, and again, they’re shown to be a thoroughly devoted and healthy couple. I found the whole thing pretty innocuous and, again, funny, but your mileage may vary.

There’s also a rather strange tendency to force Yuki into women’s clothing, which everyone else reacts to as if it’s extremely attractive (he hates it). I don’t know; it’s funny for how over-the-top it is, but it felt to me like a cultural gap, and again your mileage may vary.

And I suppose it could be argued that the ending is a little too lenient on certain characters, but again that seems to be more intentional in keeping with the themes of forgiveness and compassion and moving beyond trauma.

As I say, I’ll probably do a separate piece going into the story’s take on sex in general, but it overall seems to me to be pretty wholesome, all things considered: the main couples are very chaste and innocently sweet, the depictions of illicit sex or related matters are mostly played as being deviant and unhealthy, manifestations of emotional problems rather than signs of maturity, and so on.

I also would probably have to do a second piece on the short sequel series, though I’ll just say here that I think that one ties the original off very nicely, with a more confined story of the happy and well-adjusted offspring of the original cast reaching out to help a girl with a terrible home life.

In summary, it’s become a favorite and I’d highly recommend it. It’s very funny, very sweet, and charmingly romantic, with great characters and overall very positive themes of healing, forgiveness, and family. And it ends on one of the most perfect notes in any romance I’ve read.