1. Something to get clear in your mind is that a religious dogma is no less of a dogma because it is materialist. Evolution is, for most people, a religious dogma.

Therefore, the narrative that teaching Evolution makes students more critical or rational thinkers, as opposed to teaching religious dogma, is nonsense because evolution is a religious dogma.

2. The purpose of teaching evolution is to inculcate the established mythology of the present day. That is not to say that evolution is false (I’m overall agnostic on the subject), but it is a part of the animating myth of modernity; the frame by which modern people understand the world and themselves. This myth long pre-dates Darwin (who was embraced precisely because he gave the myth a functional narrative) and is centered around the idea of endless development from primitive origins to ever-greater supremacy. This is in contrast with the pre-modern idea, which framed the world as a descent from an original golden age.

The former, of course, is flattering to the current generation and encourages development, innovation, and revolution. The latter encourages respect for elders, ancestors, and preservation of tradition.

3. War of the Worlds is one of the essential texts of the modern mythology, since it expresses one of the core nightmares of the myth. If life develops naturally, and humans are just the peak of natural development on Earth, then there is no reason to think we won’t someday encounter another form of life that is more developed than us. In which case, humanity would inevitably lose the ‘war for survival,’ which is the worst possible outcome.

The interesting thing is that the worst nightmare of the modern myth – the existence of a higher and stronger creature than ourselves – is the basic premise of the pre-modern myths. A Medieval would be less disturbed by the Martians than a Modern because he would already have the mindset that God is immeasurably greater (that, and Medievals were more used to thinking of the world in general as something he doesn’t control).

4. I’ve been reading P.G. Wodehouse lately. Not just the Jeeves stories, but also sampling his novels, which are delightful. They strike just the right balance of laughing at the absurdities of the upperclass without a trace of contempt. The Wodehouse hero is slow-witted, but well-educated, utterly lacking in confidence, but straight as they make ’em, naive and totally unprepared for the complexities and pitfalls of life, but possessed of an instinctual sense of honour that might be thought rather more valuable. Sort of a young version of Mr. Pickwick.

I think it is in part this touch of honour, this fundamental approval of Bertie Wooster and his ilk that makes Wodehouse’s work so universally delightful. It loves what it mocks and mocks what it loves.

5. One thing Machiavelli points out in The Prince is that “A prince who is not wise himself cannot be counseled well.” That is, if a prince isn’t wise himself, he cannot be counseled into wisdom, because he needs to be wise enough to recognize good counsel in the first place.

6. On the subject of Machiavellian leadership, it struck me as I was delving into the subject how often Jesus is shown asserting dominance in the Gospels. For instance, the passage in Matthew 21, where the priests try to ask Jesus where His authority comes from, He declines to answer, not by a flat refusal, but by first posing them a question He knows they won’t give an honest answer to (since they fear admitting wrong doing on one hand and being unpopular on the other). In so doing, He flips the situation: the priests come to challenge Him and He turns it into a challenge on them, forcing them to respond. As soon as that happens, He’s won, because he’s asserted that He is the actor not the reactor (the one who knocks, so to speak): they don’t have the right to interrogate Him. But the brilliant part is that He does this in such a way as to illustrate that, even in human terms, they have no right to demand answers of Him, since they aren’t asking in good faith.

This is why what I think is one of the best depictions of Him is the moment in Ben Hur where He stares down a sadistic centurion without uttering a word. Jesus is not a meek hippy type: He’s the kind of man who can effortlessly dominate any room He enters. His meekness lies in how He directs this force of personality to our good, not in His being weak or submissive.

7.

2. I always think it telling that Hegel’s Phenomenology of Mind – which, to quote from Hegel’s Britannica article, “describes how the human mind has risen from mere consciousness, through self-consciousness, reason, spirit, and religion, to absolute knowledge” – was published literally the year before biological evolution was mooted in Lamarck’s Philosophie zoölogique. As the old saw more or less goes, each age gets the science it deserves. (Of course, nobody notices this because everyone is convinced that evolution was Darwin’s baby. Because, you know, when an idea was proposed by a Frenchman and cast into its present form by a Dutchman, of course we have to give the credit to an Englishman.)

3. Hear, hear. I remember, back in 2012, someone expressed surprise that the heroine of my Animorphs fanfic was so nonchalant about meeting the Ellimist, and I said, in part, “Remember Captain America in the new Avengers movie? We Christians are hard people to impress.”

6. With the added finesse, of course, that the true answer to the scribes’ question is the same as the correct answer to Jesus’s question, only more so. It’s wonderful watching Him work. (And, seriously, is there anything in Ben-Hur that *isn’t* among the best at what it does? People sneer at the Academy for giving it a record number of Oscars, but, honestly…)

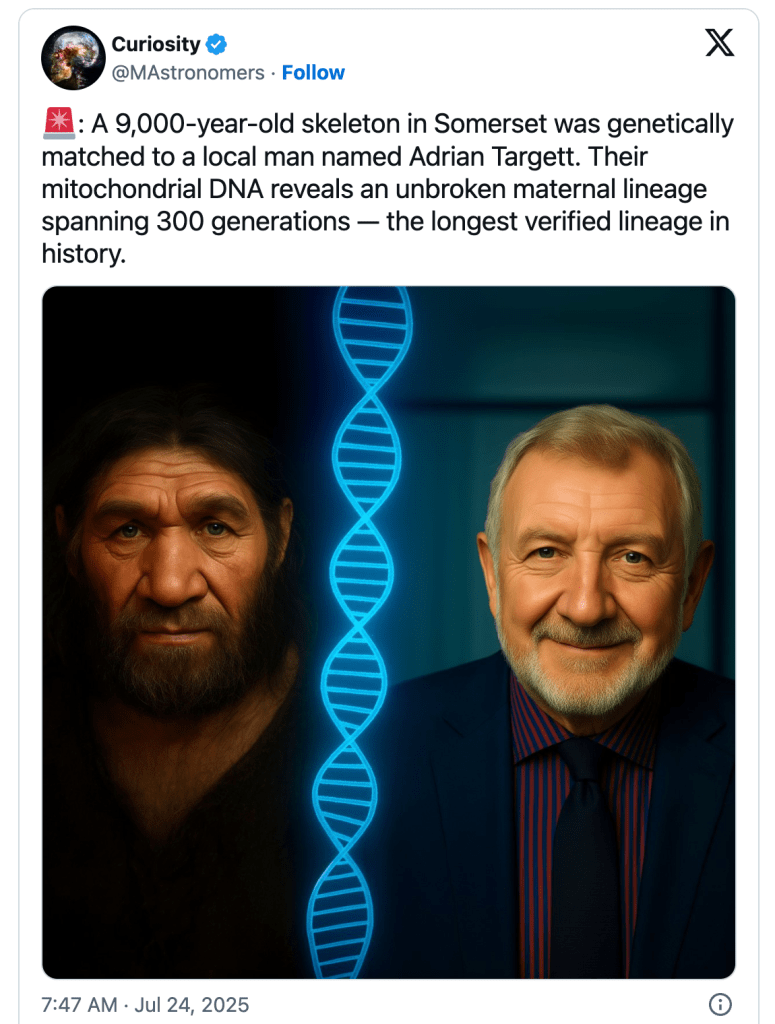

7. Well, good for Adrian. Now we just need to get all the public officials in Somerset to resign their jobs and give them to him…

LikeLiked by 1 person